I’m making the field trip optional, as I’m still now well and cannot make it tomorrow. Please see email for details. Enjoy the show!

I’m making the field trip optional, as I’m still now well and cannot make it tomorrow. Please see email for details. Enjoy the show!

Check out this giant new mural, “28 Blocks,” by Garin Baker, honoring the men who assembled the marble sculpture inside the Lincoln Memorial. It faces the Metropolitan Branch Trail where it intersects New York Avenue NE.

Check out this giant new mural, “28 Blocks,” by Garin Baker, honoring the men who assembled the marble sculpture inside the Lincoln Memorial. It faces the Metropolitan Branch Trail where it intersects New York Avenue NE.

Northeast D.C. Gets A New Mural Honoring The Workers Who Built The Lincoln Memorial Statue

J. P. Telotte, “Spatial Presence and Disney’s Oswald

J. P. Telotte, “Spatial Presence and Disney’s Oswald

Comedies,” Journal of Popular Film and Television 39.3 (2011): 141-148.

Abstracted by Ira Clark

Walt Disney and his studio had always been pioneers of animation, even long prior to their famed success with the Mickey Mouse cartoons. Telotte claims that Disney’s most significant advancement was spatial awareness and subsequent utilization of the entire film frame to enhance storytelling ability. This is utilization is further described as “positive negative space,” unlike in contemporary cartoons where so called “negative spaces” went unused entirely (143). Oswald and successive Disney characters would make this “negative space” positive by filling it with their gags and antics. Telotte notes three cases where Disney’s spatial awareness is distinct and contributive, through staging, use of shadows, and body morphing. Beginning with Oswald, Disney cartoons contained unmistakable “staging” (143), as objects now had arranged purpose within the frame, achieved through storyboards, another pioneering Disney technique, which allowed for preplanning. Staging allowed Disney to create more immersive scenes, such as when a myriad of thrown objects from off-screen engulfs the space around Oswald. In more complex films such as the 1928 Ossie of the Mounted, staging facilitates elaborate scenes as animators plan out multilayered scenes with distinct fore, middle, and backgrounds which allowed for minimal negative space and a more enthralling visual narrative. Secondly, spatial awareness was demonstrated by characters now employing shadows in their antics. A creative example of this is seen in the 1928 silent cartoon Bright Lights where shadows become important plot devices, allowing Oswald to sneak into a theater by “lifting up” his own shadow, hiding underneath, and walking right in. Finally, in what would become trademark Oswald humor, body morphing would entail character’s limbs becoming unnaturally stretched or enlarged to encompass the entirety of the frame. In another 1928 production, Fox Chaser, Oswald’s legs are ludicrously stretched across the screen as one foot is stuck on a ladder and another on a galloping horse. These “spatial gags” (146) both address negative space and add comedic value. Telotte argues that animation scholars have overlooked the early use and impact of this “spatial presence” and its origins within the Oswald cartoons.

Jennifer L. Roberts, “Failure to Deliver: Watson and the Shark and the Boston Tea Party,” Art History 34.4 (2011): 674-95.

Jennifer L. Roberts, “Failure to Deliver: Watson and the Shark and the Boston Tea Party,” Art History 34.4 (2011): 674-95.

Abstractd by Tanner Stump

In Roberts’ article, the paintings of John Singleton Copley during pre-revolutionary war times between the 1760s and 1770s reflect the transatlantic between America and Britain. The writer claims that Copley’s tabletop paintings (1760s – early 1770s) reflect the smooth trade and pronounced connection between the two areas, while the painting Watson and the Shark (1778) represents the “catastrophe in Anglo-American material relations” through the puissant acts of the Boston Tea Party (676). Roberts’ explains that the British reacted more favorably to Copley’s paintings that had less attention grabbing aspects in the lower half of the painting, and he made a habit of conforming to this notion throughout the series of paintings proving the influence British culture had in America. The writer also notes that Copley’s tabletops have such a smooth surface that they reflect the objects resting on them. This symbolizes the fluid relationship between Britain’s colonies and Britain itself. Roberts argues that Copley broke the theme when with Watson and the Shark which contained an elaborate lower half that represented the schism between America and Britain that came with the Tea Party. Furthermore, the writer draws parallels between Copley’s literal connections in Boston through family that pulled him into the conflict and ultimately forced him to flee after the Tea Party. Roberts argues that these connections made Copley desire to create a memorial painting for this conflict that accurately depicts the events, but he concluded that the intensity and passion of the issue would cause the painting to be “inevitably ‘misconstrued’” (687). For this reason, the writer claims that Copley drew from the commission of Brook Watson, who owned the tea in the Tea Party, to construct a painting of a non-fatal shark attack Watson personally experienced in Havana in order to indirectly depict the Boston Tea Party through the two events’ parallels concerning location, characters and destructive actions. Roberts claims that the thematic path of Copley’s paintings during this time period illustrated the ephemeral transatlantic relations between America and Britain while concluding that the sea was “an unbridgeable space” that these relations could not surmount (694).

Weber, Jonetta D., and Robert M. Carini. “Where Are the Female Athletes in Sports Illustrated? A Content Analysis of Covers (2000-2011).” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 48.2 (2013): 196-203.

Weber, Jonetta D., and Robert M. Carini. “Where Are the Female Athletes in Sports Illustrated? A Content Analysis of Covers (2000-2011).” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 48.2 (2013): 196-203.

Abstracted by Juliet Day

Weber and Carini argue that, although women are represented in Sports Illustrated, the magazine still fosters social inequality between male and female athletes. They expose the double standard Sports Illustrated exhibits by documenting how it portrays men versus women on its cover. They reviewed every Sports Illustrated cover from 2000 to 2011 and from 1954 to 1965 and tracked how many men were on the cover versus how many women. They excluded Sports Illustrated’s annual swimsuit issue because “women were not portrayed in an athletic manner.” They then divided the women into two groups: athletes and other women (an anonymous woman, a sports fan, etc.), as well as whether the women were pictured by themselves or with men. Women appeared on 4.9% of Sports Illustrated covers between 2000 and 2011 (N=716) and only 2.5% had women as the primary image. This is over 50% lower than the percentage of women on the cover between the years of 1954-1965 (N=588), which was still only 12.6%. One explanation as to why the percentage of women represented has decreased since the 1950s is that Sports Illustrated narrowed the scope of the sports it covers from a wide range of sports to mainly featuring basketball, football, and baseball. Weber and Carini then explore how women were portrayed in Sports Illustrated when included, and what message the magazine sends about gender. For example, they note the difference between an athletic-looking woman holding sports equipment on the cover, versus a scantily dressed, seductive-looking woman. While Sports Illustrated promotes sports as a way to achieve health and fitness as well as personal empowerment, women are not necessarily depicted solely for their athletic abilities, but rather for how they look or how they are posed. They cite as an example the case of skier Lindsey Vonn, who was photographed on her skis, but posed in a provocative way, as opposed to a male skier photographed in action. Lastly, Weber and Carini assert that their data is consistent with that of other similar studies about female athletes portrayed in both Sports Illustrated and in other media.

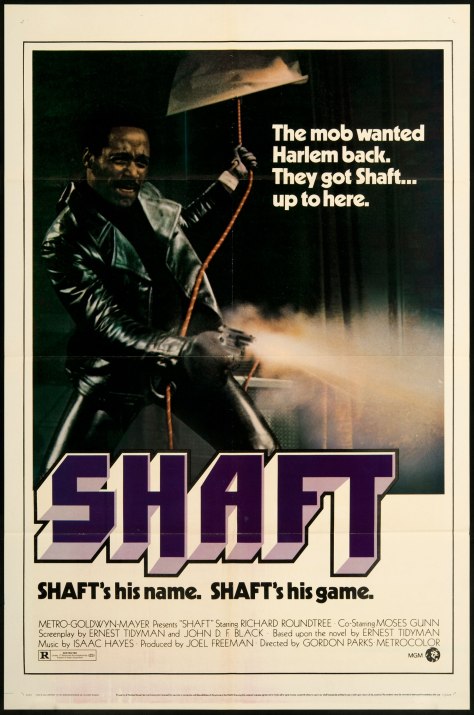

Ben’s Chili Bowl, a DC institution, hosts a monthly Classic Black Cinema Night; the next one is May 1: SHAFT! (1971), starring Richard Roundtree, directed by Gordon Parks, music by Isaac Hayes.

Film is free–but they encourage donations to Ben’s Chili Bowl Foundation, a 501c3 non-profit that supports local community groups is the city. Food is cheap!

Details:

Ben’s Chili Bowl Back Room / 1213 U Street NW

Monday, May 1

6:30 PM – Food and Film Introduction

7:00 – 9:00 PM – A Classic Black Film: SHAFT!

9:00 PM – Film Discussion

9:30 PM – Retire to Ben’s Next Door

For the story of Shaft and its impact, listen to the Studio 360 feature, Shaft & Present.

Okay, so not everything in a newspaper/magazine’s layout is intentional. For example:

And they just get worse from there: http://www.thepoke.co.uk/2016/02/12/27-hilarious-publishing-layout-failures-history/

What does (or can) a map say about ongoing events on the ground? What argument does a map make? What facts does it emphasize or hide? Here’s an interesting–and invested–take from the Dakota Sioux protests (link above).

You must be logged in to post a comment.